No Excuses! Lay Judges Reject Exhaustion as a Reason for Failing to Help Others

Imagine that your spouse has promised that they will wash the dishes cluttering your sink this evening; but, when they arrive home exhausted after a stressful day of back-to-back meetings and skipped meals, they try to pawn the responsibility back off on you. Would you soften your judgment of your spouse on account of their fatigue?

We find that the court of moral opinion is unsympathetic to the exhausted: Across several studies, we found that people judged actors who were fatigued and did good or bad deeds as equivalently (im)moral as those who were refreshed.

Photo by Tirachard Kumtanom from Pexels

Photo by Tirachard Kumtanom from Pexels

Sniping spouses bandy back and forth arguments of all flavors during moments of marital discord. As dishes lie unwashed in the sink, one well-worn exculpation can sneak its way into conversation: I had a long day at work; I’m exhausted—can’t you just take care of it? The foundation of the argument is simple: Being tired may seem to intuitively justify giving a person a bit more space to act less kindly or more selfishly than they might otherwise. If people perceive fatigue as constraining prosocial behavior, it is reasonable to assume that they may soften their negative judgments of fatigued others who fail to act prosocially. Yet, in study after study, we found no such pattern: Observers’ judgments were unaffected by the perceived fatigue of actors.

Why might fatigue matter for moral judgments?

Witnessing a moral failure by a fatigued person provides an observer with ambiguous information: It is unclear whether the actor is generally undisposed to act kindly (an internal attribution about the actor’s traits) or if they were just too exhausted to help in the moment (an external attribution about the influence of the situation). The ambiguity about whether an actor lacked the disposition or ability to act could reduce blame.[1] Conversely, witnessing a moral action by a fatigued person might provide extra evidence of goodness (This person helped me despite their fatigue—they must be truly moral!), earning them “moral extra credit.”

Why might fatigue not affect judgments?

Moral judgments can be thought of as strategic estimates of future behavior—Can I trust this person tomorrow?[2] Sometimes, the best predictor of future behavior is past behavior, independent of fatigue. Moreover, if people use fatigue to excuse moral failings, then people facing temptation might exhaust themselves—or claim exhaustion—to get away with misdeeds, chipping away at moral accountability. Indeed, research shows that people are highly motivated to hold people to moral standards to keep cooperative systems going, and they may therefore be motivated to blame and praise good and bad behavior regardless of fatigue.[3]

We put these possibilities to the test

First, we confirmed that people believe fatigue reduces helping.[4] In a pretest, participants (N = 182) read vignettes describing either fatigued or refreshed actors (e.g., actors who either spent all morning swimming laps or relaxing poolside) who could provide modest help to others or act selfishly (e.g., giving a dollar to a smiling young busker or rudely rushing by). Participants reliably distinguished between actors who were fatigued or refreshed (and did so in all of our studies), regardless of whether fatigue came from physical exertion (swimming), stress (harrowing traffic), or mental effort (working long periods without refreshment). Critically, people predicted that fatigued actors would be less prosocial than refreshed actors. Lay people detect fatigue and assume it reduces helping, in line with other empirical work.[5]

Next, in a new study (N = 111), we had participants judge the morality of fatigued or refreshed actors who either helped or refused to help others (e.g., covering a shift for a coworker in need). Participants also indicated how much actors themselves deserved help, and their own likelihood of helping actors in hypothetical later situations. Turnabout is fair play, after all.

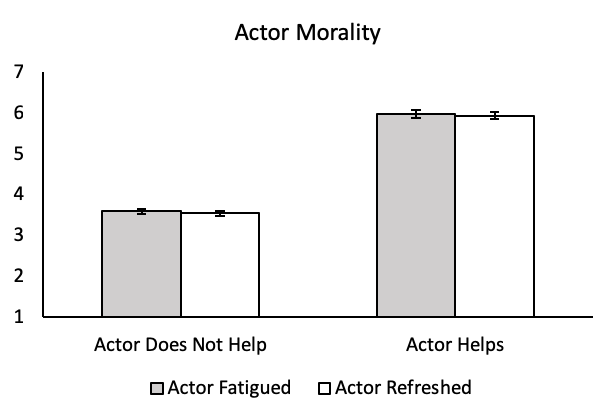

The results were clear: Participants rated helpful actors as more moral than unhelpful actors (as expected), but, critically, actor fatigue had no impact on morality ratings (Figure 1). The same pattern emerged for ratings of how much actors deserved help and how likely participants would be to help them. Despite participants recognizing that actors were exhausted, fatigue did not provide an excuse for unhelpful actors or earn helpful actors a moral bonus. It was actor deeds, not actor fatigue, that mattered for moral judgments. (Statistically savvy readers will note from the tiny error bars that the effect size for actor behavior was enormous, average ηp2 = .72, but the effect for actor fatigue was miniscule, average ηp2 = .01.)

Figure 1. Perceived Actor Morality across the Actor Fatigued vs. Refreshed and Helping vs. No Helping Conditions, Study 1. Error bars reflect standard errors.

We ran half a dozen more studies to clarify whether these findings held for both major and minor levels of fatigue (e.g., running a triathlon versus swimming light laps) and major and minor degrees of helping (e.g., dedicating a full day to help a neighbor in need versus providing a quick favor, N = 499), for actors who performed bad deeds instead of who failed to perform good deeds (N = 382), and using video presentations of actors instead of written scenarios (N = 151). Each study demonstrated the same pattern: Participants recognized when actors were fatigued, but this knowledge had no influence on moral judgments. These findings even held for participants who believe that willpower can be exhausted (N = 170).

Conclusion

These results suggest that fatigue does not excuse bad behavior or make good behavior more impressive: Others will judge you by your deeds no matter how exhausted you are. The excuse “it was long day at work” carries no water. Even after working overtime, when your partner asks you to take Rover for a walk, a nod and a smile are the safest bet.

References

[1] Weiner, B. (1995). Judgments of responsibility: A foundation for a theory of social conduct. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

[2] Uhlmann, E. L., Pizarro, D. A., & Diermeier, D. (2015). A person-centered approach to moral judgment. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 10, 72-81. doi:10.1177/1745691614556679

[3] Clark, C. J., Luguri, J. B., Ditto, P. H., Knobe, J., Shariff, A. F., & Baumeister, R. F. (2014). Free to punish: A motivated account of free will belief. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 106, 501-513. doi:10.1037/a0035880

[4] Goldstein-Greenwood, J., & Conway, P. (in press). Fatigue compatibilism: Lay perceivers believe that fatigue predicts—but does not excuse—moral failings. Social Cognition.

[5] DeWall, N. C., Baumeister, R. F., Gailliot, M. T., & Maner, J. K. (2008). Depletion make the heart grow less helpful: Helping as a function of self-regulatory energy and genetic relatedness. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 34, 1653-1662. doi:10.1177/0146167208323981