Why we’d buy a microwave from BODIKA_1996 but not from KODIBA_1996 – Articulation movements and their effects on judgments and decisions

Editorial Assistants: Lukas Repnik and Zoey Chapman.

Note: An earlier version of this article has been published in the German version of In-Mind.

People like inward-oriented articulation movements (e.g., in BODIKA – Lips → Tongue → Throat) more than outward-oriented articulation movements (e.g., in KODIBA – Throat → Tongue → Lips). This effect has an impact on various judgments and decisions in everyday life - but why is “in” better than “out”?

Imagine you’re searching on eBay for a used microwave. A private seller with the username BODIKA_1996 offers a good model at a reasonable price. You scroll a bit further and find another seller with the username KODIBA_1996, offering a similar model for the same price. Which seller would you be more likely to contact?

Most people in this situation would prefer BODIKA_1996 [1]. But why? Both usernames are entirely fictional and reveal very little about the person behind them. The usernames are also highly similar – in fact, they only differ in the position of the letters “B” and “K”. And yet, most people would rate BODIKA_1996 as more trustworthy and would want to contact them first [1].

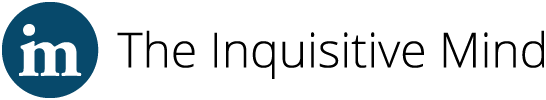

The reason lies in the different articulation movements of BODIKA and KODIBA. A relatively new branch of research in psychology has shown that people prefer inward-oriented articulation movements over outward-oriented articulation movements [2], [3]. In BODIKA, the first consonant, “B,” is formed at the lips, the second consonant, “D,” with the tongue at the front of the palate, and the third consonant, “K,” at the back of the throat. When pronouncing BODIKA, these different points of articulation in the mouth form a movement from the outside towards the inside. In KODIBA, the order of articulation points is reversed (throat → front palate → lips), creating a movement from the inside towards the outside. People seem to prefer inward over outward articulation movements, a phenomenon known as the “articulatory in–out effect”.

Figure 1: Consonants are articulated at different places in the mouth - for example, at the lips, with the tongue on the front palate, or at the back of the throat.

Figure 1: Consonants are articulated at different places in the mouth - for example, at the lips, with the tongue on the front palate, or at the back of the throat.

The Articulatory In-Out Effect

Different consonants can form inward- or outward-facing words in English – for example, MENUKI and PATIGO (inward) or KENUMI and GATIPO (outward). Try pronouncing these words to yourself. Do you notice the difference in how you articulate them? Research shows that people generally like words like BODIKA, MENUKI, or PATIGO more than words like KODIBA, KENUMI, or GATIPO when asked how much they like these kinds of words. Interestingly, this preference emerges despite the words containing the exact same vowels and consonants – the only difference is the order of the consonants.

However, the articulatory in-out effect is not limited to the English language. It also appears in other languages, including Portuguese [4], German [2], Japanese [5], and Turkish [6]. Of course, researchers must ensure that speakers pronounce each letter with the correct sound when studying this effect in other languages. For example, the “R” is also articulated in the throat in German but not in English. Interestingly, the articulatory in-out effect seems to occur regardless of whether we read the word, say it aloud ourselves, or listen to someone else say it [7]. And it does not even require full words. The effect has been found with abbreviations (e.g., BK) and even with word fragments (B _ _ _ K_) [7], [8].

The effect does not just influence how we rate words or abbreviations – it also affects everyday social judgments and consumer decisions. For instance, people tend to perceive those with inward-articulated names as friendlier and nicer [4] and view eBay sellers with inward-articulated usernames as more trustworthy [1]. They even judge food items labeled with inward-sounding names to be more appetizing [9]. So, the effect seems to influence many everyday judgments and decisions.

It is fascinating that people are unaware of how articulation movements influence their judgments [10]. We do not know why we find BODIKA_1996 more trustworthy than KODIBA_1996 – it just feels like BODIKA_1996 is a nicer, more helpful person [4].

Figure 2: Should I entrust this seller with my payment details? The articulation movements in the username also influence this decision.

Figure 2: Should I entrust this seller with my payment details? The articulation movements in the username also influence this decision.

One limitation, however, is that the effect becomes significantly weaker once more relevant and diagnostic information is available. For example, suppose the eBay seller BODIKA_1996 has a recommendation rate of only 20%, but KODIBA_1996 has a recommendation rate of 95%. In that case, the impact of the articulation movements will be minimal or may even disappear entirely [1]. Recent research also shows that the effect vanishes when the evaluated words have actual meaning [11]. So, it is questionable whether you genuinely like your neighbor MONIKA just because of her name’s articulation movements (lip → tongue → throat), or whether you dislike your coworker KALEB just because of his name’s articulation movements (throat → tongue → lip).

Why is “in” better than “out”?

Because the effect appears across different languages, materials, and types of judgment, interest in the articulatory in-out effect has grown in recent years. However, research still has not agreed on why the effect occurs [3].

The original theory behind the effect is that inward articulation movements resemble the movements involved in eating and swallowing [2]. Since people usually associate consuming food with positive outcomes (e.g., feeling full), they may also perceive inward articulation movements positively. And if inward articulation is reminiscent of eating, outward articulation logically resembles… right – vomiting or spitting, which generally feels unpleasant. Findings support this explanation by showing that the effect is stronger when people evaluate products meant to be consumed inwardly (e.g., soda) than those consumed outwardly (e.g., chewing gum) [12]. However, the effect is not influenced by whether a person is hungry or disgusted [8].

Figure 3: Do we like inward-oriented articulation movements because they resemble eating and swallowing?

Figure 3: Do we like inward-oriented articulation movements because they resemble eating and swallowing?

Another theory is that words with inward articulation movements are easier to pronounce [13]. People generally like things that are easy to process [14]. In language, easier processing can come from easier pronunciation. The same principle could apply here – “in” is easier than “out”. Findings support this theory by showing that people indeed perceive inward words as easier to pronounce [13]. However, ease of pronunciation alone doesn’t fully explain the effect. For instance, people find BODIPA (which lacks a consistent inward/outward articulation movement) just as easy to pronounce as the inward word BODIKA. However, in terms of preference, BODIKA is liked significantly more than BODIPA [10]. That suggests pronunciation ease is not the only factor behind the in-out effect.

Figure 4: People prefer words that are easy to articulate.

Figure 4: People prefer words that are easy to articulate.

A third theory claims that the effect has nothing to do with articulation movements at all but rather with specific consonants [8]. People tend to like front consonants such as “B” or “P” more than “K” or “G”. These consonant preferences have a stronger impact when they appear at the beginning of a word. For example, this theory would predict that BODIKA is preferred over KODIBA simply because it starts with a “B” instead of a “K”. Later consonants (like the second “K” or “B”) have less influence. Indeed, with word fragments like B _ _ _ K _ and K _ _ _ B _, more front consonants like “B” and “P” tend to result in higher ratings. People, for instance, prefer B _ _ _ P _ over B _ _ _ K _ [8].

However, this pattern breaks down when people evaluate full, pronounceable words. For instance, BODIKA is preferred over BODIPA, even though BODIPA contains both “B” and “P” – two front consonants [15]. These findings suggest that preference for certain consonants alone cannot explain the in-out effect either.

Figure 5: Although people like some consonants more than others, this cannot explain the articulatory in-out effect.

Figure 5: Although people like some consonants more than others, this cannot explain the articulatory in-out effect.

Conclusion and Outlook

In sum, the articulatory in-out effect appears to be a robust phenomenon that can influence various judgments and decisions in everyday life. However, the current theories still cannot fully explain why the effect happens. So, where do we go from here?

Future research could explore the effect across different language families. For instance, if the effect does not appear in Arabic languages, researchers could examine how Arabic differs from non-Arabic languages to identify potential explanations. It would also help to systematically analyze how often inward vs. outward articulation patterns appear in different languages and whether they occur more frequently in certain kinds of words. Maybe inward patterns are more common in positive words, which could explain our preference for them even in made-up words. Studies with children at different stages of language acquisition could also help reveal the underlying processes behind the in-out effect.

Until researchers conduct these studies, one thing remains clear: articulation movements influence how we judge and decide – a point worth remembering when you create a brand name or set up your eBay profile. So, if you plan to sell a microwave anytime soon, take the user BODIKA_1996 as an example and choose a username where the consonants are arranged from the front to the back – with an inward articulation movement.

Bibliography

[1] R. R. Silva and S. Topolinski, “My username is IN! The influence of inward vs. outward wandering usernames on judgments of online seller trustworthiness,” Psychology & Marketing, vol. 35, pp. 307–319, 2018, doi: 10.1002/mar.21088.

[2] S. Topolinski, I. T. Maschmann, D. Pecher, and P. Winkielman, “Oral approach–avoidance: Affective consequences of muscular articulation dynamics.,” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, vol. 106, pp. 885–896, 2014, doi: 10.1037/a0036477.

[3] M. Ingendahl, T. Vogel, and S. Topolinski, “The articulatory in-out effect: replicable, but inexplicable,” Trends in Cognitive Sciences, vol. 26, no. 1, pp. 8–10, 2022, doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2021.10.008.

[4] M. V. Garrido, S. Godinho, and G. R. Semin, “The ‘ins’ and ‘outs’ of person perception: The influence of consonant wanderings in judgments of warmth and competence,” Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, vol. 82, pp. 1–5, 2019, doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2018.11.004.

[5] K. Motoki and A. Pathak, “Articulatory global branding: Generalizability, modulators, and mechanisms of the in-out effect in non-WEIRD consumers,” Journal of Business Research, vol. 149, pp. 231–239, Oct. 2022, doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2022.05.030.

[6] S. Godinho, M. V. Garrido, and O. V. Horchak, “Oral approach avoidance: A replication and extension for Slavic and Turkic phonations.,” Experimental Psychology, vol. 66, pp. 355–360, 2019, doi: 10.1027/1618-3169/a000458.

[7] S. Topolinski and L. Boecker, “Minimal conditions of motor inductions of approach-avoidance states: The case of oral movements.,” Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, vol. 145, pp. 1589–1603, 2016, doi: 10.1037/xge0000217.

[8] I. T. Maschmann, A. Körner, L. Boecker, and S. Topolinski, “Front in the mouth, front in the word: The driving mechanisms of the in-out effect.,” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, vol. 119, no. 4, pp. 792–807, 2020, doi: 10.1037/pspa0000196.

[9] S. Topolinski and L. Boecker, “Mouth-watering words: Articulatory inductions of eating-like mouth movements increase perceived food palatability,” Appetite, vol. 99, pp. 112–120, 2016, doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2016.01.018.

[10] M. Ingendahl, T. Vogel, and M. Wänke, “The Articulatory In-Out Effect: Driven by Articulation Fluency?,” Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, vol. 99, p. 104273, 2022, doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2021.104273.

[11] J. A. A. Engelen, “The In-Out Effect in the Perception and Production of Real Words,” Cognitive Science, vol. 46, no. 9, Art. no. 9, 2022, doi: 10.1111/cogs.13193.

[12] S. Topolinski, L. Boecker, T. M. Erle, G. Bakhtiari, and D. Pecher, “Matching between oral inward–outward movements of object names and oral movements associated with denoted objects,” Cognition and Emotion, vol. 31, no. 1, pp. 3–18, Jan. 2017, doi: 10.1080/02699931.2015.1073692.

[13] G. Bakhtiari, A. Körner, and S. Topolinski, “The role of fluency in preferences for inward over outward words,” Acta Psychologica, vol. 171, pp. 110–117, 2016, doi: 10.1016/j.actpsy.2016.10.006.

[14] R. Reber, N. Schwarz, and P. Winkielman, “Processing Fluency and Aesthetic Pleasure: Is Beauty in the Perceiver’s Processing Experience?,” Personality and Social Psychology Review, vol. 8, pp. 364–382, 2004, doi: 10.1207/s15327957pspr0804_3.

[15] M. Ingendahl and T. Vogel, “The articulatory in-out effect: Driven by consonant preferences?,” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, vol. 122, no. 2, pp. e1–e10, 2022, doi: 10.1037/pspa0000276.

Picture Sources

Figure 1: Figure 1 in Ingendahl, Vogel, & Topolinski (2022) https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2021.10.008

Figure 2: https://pixabay.com/de/illustrations/internet-computer-bildschirm-1593384/

Figure 3: https://pixabay.com/de/photos/apfel-beissen-di%C3%A4t-essen-gesicht-15687/

Figure 4: https://www.freepik.com/free-photo/person-eating-sweet-candy-desert_3148...

Figure 5: https://www.pexels.com/de-de/foto/brown-scrabble-boards-mit-buchstaben-2...