Politics Doesn’t Define How Most People See Themselves

Editorial Assistants: Charikleia Lampraki and Elena Benini.

The social groups to which we belong shape how we see ourselves, but which groups matter most? We show that political parties and ideology are not the first things that come to mind when people think about themselves. Instead, identities like nationality and age are far more central and may help bridge political divides.

Political divides based on party affiliations or political views are prominently featured in news headlines and public discourse globally, and increasingly so within UK politics. It would be easy to assume then that political

affiliation or orientation determine how citizens see themselves. But is that actually the case? Do people primarily view themselves through a political lens - as Labour or Conservative, left or right - or do other aspects of identity, such as nationality,

gender, cultural background, or occupation, weigh more heavily in shaping individual identities?

Research in psychology suggests that the groups people belong to can become an important part of how they think about themselves [1].

Social Identity Theory proposes that our sense of self is shaped not only by personal characteristics, such as our personality or values that we hold, but also by the

social groups we identify with [1]. Accordingly, a person’s

self-esteem is tied to the status of their groups, which is why people are often motivated to see their groups in a positive light. This can foster feelings of solidarity with fellow group members, but it can also lead to conflict when the group is criticised or competes with others [2].

These ideas have been widely applied to politics. Political scientists often distinguish between two ways in which people relate to political parties [3]. One perspective sees party affiliations as the result of people’s values and policy preferences: individuals support the party that best reflects what they believe. The other perspective treats party

affiliation as a

social identity, something that can form early in life and remain stable even when political issues or party positions shift. There is evidence that many people view their political orientation and preferences as an important part of their (social) identity [4]. But people also belong to other

social groups, and it is likely that not all of them strongly influence how they generally see themselves. Even if politics matters in certain contexts, it may not be the most important part of one’s self-image. Recognising which identities voters find most important can influence how political debates unfold and how political messages are received.

To find out which aspects of identity matter most to people in the UK, Public First collected a representative

sample of 2,009 adults across the country in April 2025. Respondents were shown eight lists of four randomly selected identity facets - such as nationality, age,

gender, ethnicity, region, political views, religion, and social class - and, for each set, asked to select which felt most and least central to how they see themselves. They also indicated which single aspect they considered most important overall. Note that all statistics reported in the text and figures were weighted to reflect the demographic makeup of the UK population.

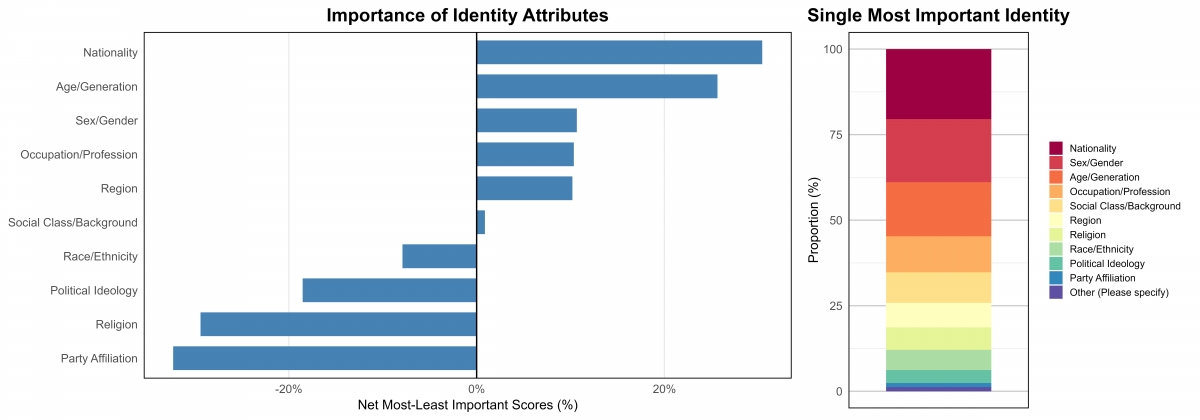

The results below illustrate how different identity attributes ranked, both in relative terms and when respondents were asked to focus on just one defining characteristic (see Figure 2). Most respondents selected their nationality as central to how they see themselves (20.4%), followed by

sex /

gender (18.5%), age/generation (15.8%), and occupation/profession (10.5%). In contrast, political identities played only a minor role. Party

affiliation and political ideology consistently ranked among the least important dimensions across both metrics, with fewer than 5% of respondents selecting them as their defining

social group. In an era often described as marked by sharp political divisions, it is striking how few people view their party or political ideology as core to their identity. That doesn’t mean that political identities are generally unimportant - they clearly matter particularly in political contexts - but many people don’t think political views define who they are. Similarly, while nationality, age or

gender may not be salient in every

domain of life, many of the respondents regard them as stable and meaningful parts of their identity. Fig. 2. Relative and absolute importance of the different social identities. Identity facets in both panels are ordered from most to least important along the y-axis.

Fig. 2. Relative and absolute importance of the different social identities. Identity facets in both panels are ordered from most to least important along the y-axis.

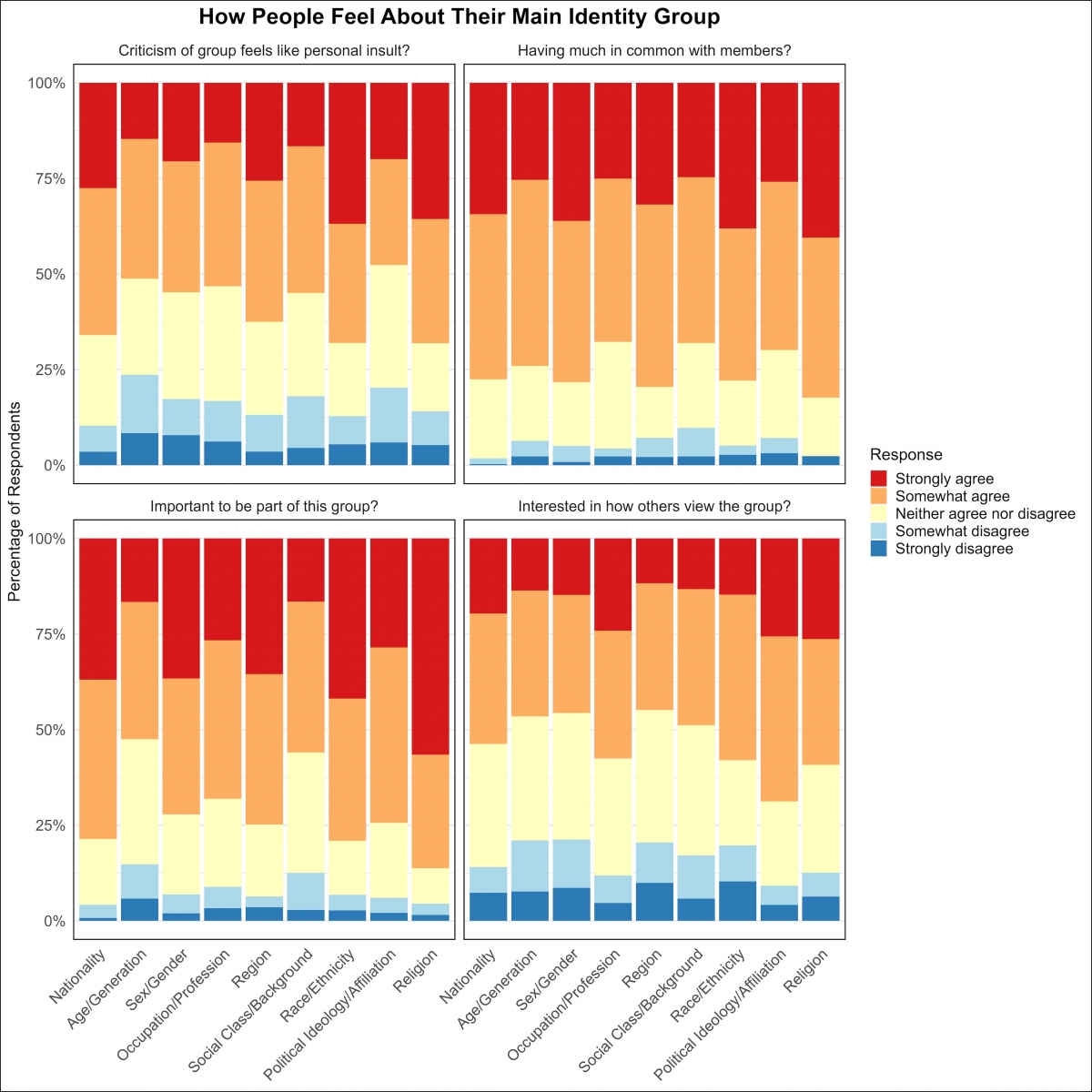

To understand what it means when someone sees an identity as central, we looked more closely at how respondents relate to the identified groups and how emotionally attached they are to them (see Figure 3). What sets nationality apart is not just how frequently it was selected as a core aspect of identity, but also the intensity of feelings associated with it. Among those who identified nationality as their most important group, about half cared how others viewed the group, and a majority agreed that they have a lot in common with other group members and that being part of the group was personally important - a pattern we also observe for other identities. But nationality stands out in how strongly people who see it as central to their identity react to criticism: 66% of these respondents said that criticism of the group would feel like a personal insult. Only religion (68.1%), race/ethnicity (68.0%), and region (62.5%) elicited similar emotional reactions - but far fewer people selected those as core aspects of their identity. It contrasts with identities like political ideology/

affiliation (47.7%) or age/generation (51.2%), where such reactions were far less common. Reactions to criticism of one's own

social group are a meaningful indicator of identity strength. They can capture how important a particular group label is for one's self-image and are an indicator of the emotional significance associated with an individual’s group membership [2].  Fig. 2. Feeling about the group that respondents considered the single most important to the way they see themselves.

Fig. 2. Feeling about the group that respondents considered the single most important to the way they see themselves.

Overall, while political identities clearly matter, particularly in political contexts, our research suggests they are not the primary lens through which most people view themselves. Instead, identities rooted in nationality, age,

gender, and occupation often feel more central and emotionally resonant. Our findings challenge the

perception that political or ideological divides are on everybody's mind as society's main fault lines - a belief that can itself fuel political division [4]. Many people relate more strongly to other identities that, while likely linked to politics, are less explicitly partisan and potentially more inclusive and widely shared. Yet, the meanings of categories like nationality or

gender are neither fixed nor universally understood. Their interpretations are continually shaped and contested in politics, in public discourse, and in everyday life. Engaging with these shared identities and countering attempts to use them in exclusionary ways or to stir further conflict could offer a path toward reducing societal division going forward.

Bibliography

[1] H. Tajfel, “Social identity and intergroup behaviour,” Social Science Information, vol. 13, no. 2, pp. 65–93, 1974, doi: 10.1177/053901847401300204.

[2] M. B. Brewer, “The social psychology of intergroup relations: Social

categorization,

ingroup bias, and

outgroup

prejudice,” in Social Psychology: Handbook of Basic Principles, 2nd ed., A. W. Kruglanski and E. T. Higgins, Eds. New York, NY, USA: Guilford Press, 2007, pp. 695–715.

[3] L. Huddy, “From social to political identity: A critical examination of

social identity theory,” Political Psychology, vol. 22, no. 1, pp. 127–156, 2001, doi: 10.1111/0162-895X.00230.

[4] J. Lees and M. Cikara, “Inaccurate group meta-perceptions drive negative

out-group attributions in competitive contexts,” Nature Human Behaviour, vol. 4, no. 3, pp. 279–286, 2020, doi: 10.1038/s41562-019-0766-4.

Figure Sources

Figure 1: https://pixabay.com/illustrations/diversity-people-group-silhouettes-554...

Figure 2: Figure self-generated from the data.

Figure 3: Figure self-generated from the data.