Starting early: How caregivers can support their children's emotion regulation

Editorial Assistants: Lukas Repnik and Zoey Chapman.

Note: An earlier version of this article has been published in the German version of In-Mind.

Emotion regulation in children can be challenging: screaming, loud crying, temper tantrums at the supermarket checkout - many people are familiar with such situations. What role do caregivers play in these moments, and how can they effectively support their children? The good news is that even small actions can have a lasting positive effect, strengthening children’s emotion regulation for life.

Annett Miller (43) is a mother with a full-time job. When she returns home in the afternoon, she finds her son Tim (8) sitting at the kitchen table, looking unhappy. He explains that he is sad because he received a bad grade in math. She looks at her child with a confused expression on her face. Although she, too, feels frustrated about the bad grade, she realizes that expressing this now might not be helpful. She doesn’t know how to help her son. Just like Annett, many others – whether parents, grandparents, or stepparents – have found themselves unsure of how to help in such moments. Perhaps you, too, have found yourself in a moment like this – wondering how best to respond to a child in distress.

A growing body of research indicates that the ability to regulate one’s own emotions is crucial for overall well-being and health, as well as the quality of social relationships and academic and professional success [1 – 4]. This article examines how caregivers can impact children’s emotional regulation at various levels and presents practical exercises to support this development.

How it all begins...

Children are born with immature brains, which means they have less capacity for self-regulation compared to adults. Therefore, during infancy, co-regulation by caregivers is essential. As children grow, they can increasingly apply their own emotion regulation strategies – assuming they have been taught these beforehand [1, 3]. Beyond the capacity to regulate emotions in challenging moments, basic components such as recognizing and responding to emotions are present from birth. Even infants express emotions; for instance, they may perceive sadness in their mother’s face and respond by crying. Between the ages of three and five, children begin to identify basic emotions such as joy, sadness, anger, and fear – both in themselves and in others. During the elementary school years (6–12), children develop a more nuanced understanding of their own emotions and those of others [3]. As their vocabulary grows, opportunities for emotional exchange increase, and interventions become more complex and extensive for school-aged children [5]. Regulating one's emotions involves more than simply recognizing and naming them. It also requires the ability to take a step back rather than being overwhelmed, and to manage complex mental processes – such as stress-inducing thoughts – in order to regulate challenging emotions consciously. Because emotion regulation is closely linked to brain maturation, caregivers should remain patient and allow children the time they need to grow.

A key aspect of learning to regulate emotions is recognizing them as meaningful signals. Emotions tell us how we feel, how we interpret situations – whether as a challenge or a threat – and whether our basic needs are being met. The way caregivers respond to these signals strongly shapes a child’s emotional development. That’s why it helps when caregivers regularly reflect on their own behavior, for example, through short, guided exercises [4]. When children feel that their emotions are taken seriously and that they are supported in dealing with them, they are more likely to develop effective emotional regulation strategies. In this way, caregivers lay the groundwork for healthy development – including emotional well-being, strong relationships, and future success [3, 4].

The Influence on Emotion Regulation on Three Levels: From Theory to Practice

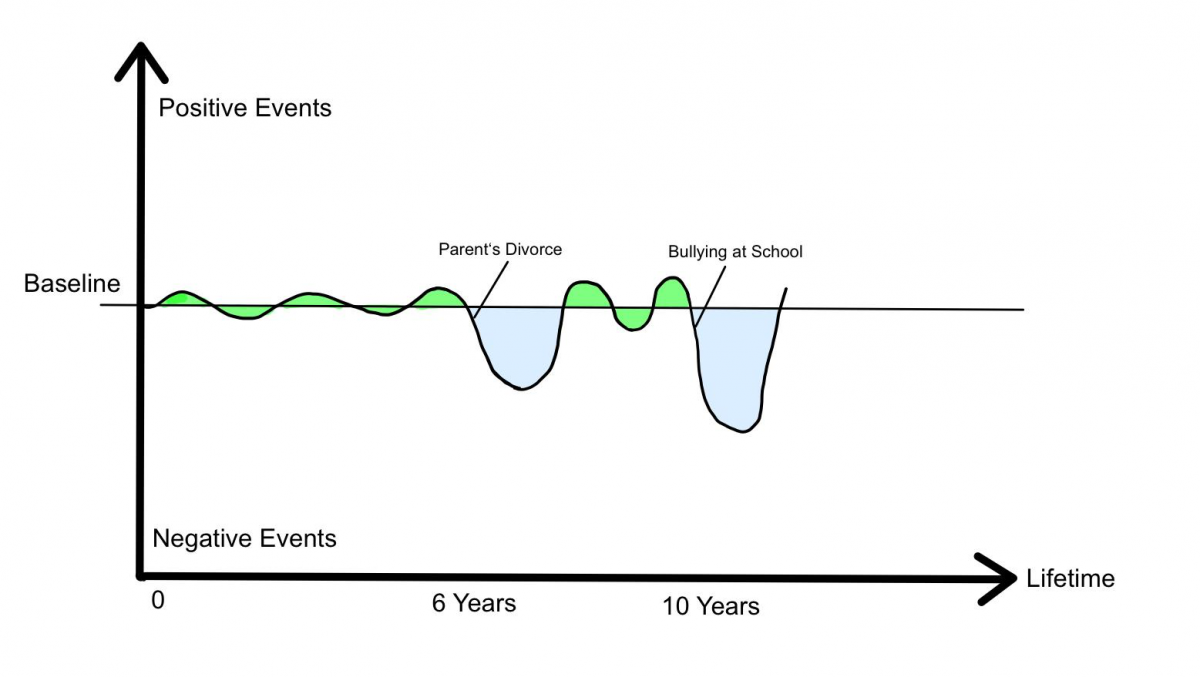

Caregivers influence the development of children’s emotion regulation on three closely interconnected levels [6]. First, the caregivers themselves and how they handle their own emotions. Second, the interaction between the caregiver and the child, with a focus on the child’s emotional experiences. And third, the social environment surrounding the child – for example, the interactions between caregivers that shape the family climate, as well as the child’s contact with peers and teachers.

Figure 2: Social-environment-child-caregiver-model

Figure 2: Social-environment-child-caregiver-model

The first level involves the primary caregivers themselves, who serve as role models, a principle referred to as observational learning in developmental psychology. By observing how caregivers manage their own emotional states, children gradually learn to understand and navigate their own emotional responses. To strengthen their emotion regulation and thus be a better role model, caregivers can use various strategies [2, 4]. These strategies fall into four categories.

Cognitive strategies focus on identifying and reframing negative thoughts that trigger unpleasant emotions. For example, a thought like "Why does everything always go wrong for me?" may lead to anger, frustration, or helplessness. Reframing such thoughts can foster positive emotions – for instance, "Life has both stressful and calmer phases. What I’m experiencing is something many others go through." This perspective encourages acceptance and emotional balance.

Emotion-focused strategies focus on acknowledging, understanding, and managing emotions constructively. Expressing and processing emotions can reduce distress and promote well-being. For example, crying when sad and realizing that the tears will eventually subside, or engaging in physical activity when angry and noticing how it channels energy, can be empowering. Additionally, writing down thoughts and feelings – also known as the "Emotional Writing Paradigm" – can be helpful. These might include brief exercises lasting around five minutes or more sustained practices such as regular journaling. Studies have shown that writing makes it easier for us to gain distance from and clarity about our emotions, helping us recognize triggers and patterns [7].

Mindfulness: Practices, such as meditation and breathing exercises, enhance the ability to stay present in the moment and consciously perceive emotions without judging them – rather than reacting automatically to emotional stimuli. For instance, reacting impulsively – such as yelling in anger or speaking without reflection – often escalates emotional situations. Numerous studies demonstrate that meditation aids in emotion regulation [8]. The goal is to learn to observe emotions from a certain distance and, based on this awareness, make conscious behavioral choices.

Social support: Sharing with others and expressing emotions help individuals feel understood and supported, facilitating the processing of unpleasant feelings. Feedback from trusted others can also encourage positive shifts in thinking and support constructive action. These strategies can be individually adapted and combined. The key is to choose approaches that align with one’s personal needs and preferences.

Let’s take a look at an example: After a stressful day at work, Annett chooses not to vent her frustration on her eight-year-old son, Tim. Instead, she sits on the living room couch, takes a few deep breaths, and tells him that she feels stressed and needs a few moments to calm down. She then takes a piece of paper and spends five minutes writing down all the thoughts and feelings racing through her mind. Afterwards, she rereads her notes without judgment. This process helps Annett identify the thoughts that fuel her stress. She then models for Tim how breathing exercises and self-reflection can bring calm. Some may wonder whether there is enough time in everyday life to apply such emotion regulation strategies. In practice, the process usually takes around ten minutes. Often, repairing relationships and rebuilding trust after emotionally hurtful moments takes considerably more time.

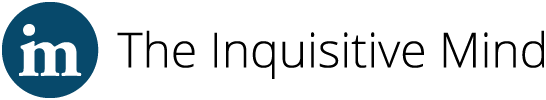

Emotions play a crucial role in current experiences and are deeply shaped by one’s biography. Caregivers need to reflect on how their own biography influences the way they respond to their children’s emotions. Biographical reflection exercises [9] help individuals identify recurring patterns and process unresolved emotional experiences. Reflecting on one’s childhood experiences, identifying triggers, developing self-compassion, and resorting to new coping strategies contribute to improved emotion regulation and foster a more empathetic approach toward children. An example is mapping one’s biography linked with positive and negative events along a timeline (see Figure 3 Life Chart).

Try this exercise, known as "Life Chart" [9]:

Materials: Blank sheet of paper; several pens

- Draw a horizontal line across the center of the paper to represent your life journey from birth to the present. Divide it into age segments. A vertical line at the starting point indicates how positively or negatively the events are remembered.

- Mark important events and life phases along this line, such as, starting school, graduation, illness, and so on.

- Represent positive events with dots above the line and negative events below it. The height or depth reflects the intensity of the experience.

- Connect these dots to form a line. Use colors or symbols to highlight special events.

- As you reflect on your life chart, consider questions such as: "Which events have left a lasting impression?", "Which still shape me today?", or "What beliefs and values emerged from these experiences?".

Beyond the caregiver’s role as a model, the second level – direct interaction with the child – is equally crucial for supporting emotional regulation [6, 10]. Caregivers need to recognize, name, validate, and help regulate their children’s emotions and underlying needs. They take on the role of an emotion coach [10, 11]. Emotions are often signals of unmet needs. For instance, a child’s need for protection might appear as fear or insecurity after an injury, whereas a need for autonomy could be expressed as anger or defiance.

The caregiver’s task is to co-regulate the emotions [12]: to interpret children’s behavior accurately, identify the child's underlying needs, and foster respectful communication that acknowledges rather than dismisses emotions ("I see you're sad. When you're ready, would you like to tell me what's bothering you?"). Children learn that expressing emotions can help their needs be understood and met, which in turn contributes to their emotional well-being. Emotion coaching also involves helping children name their feelings in everyday situations or identify where emotions are felt in their body [11]. Starting around age four to six, children can gradually be guided to regulate their emotions more independently. The importance of parents and other caregivers becomes particularly evident in the fact that interventions targeting children are more effective and have longer-lasting effects when parents are actively involved [5, 13].

For example, eight-year-old Tim comes home upset after school after a conflict with a classmate. His father sits down with him, listens attentively, and validates his feelings: "I understand you're really angry. That’s okay - it means you felt treated unfairly." Once Tim calms down, he admits feeling ashamed because he yelled and insulted his friend. Together, they discuss how Tim could respond better next time. His father suggests that Tim take deep breaths and count to ten when he is angry before replying. He also encourages Tim to talk to his friend the next day and explain what happened.

The third level focuses on the child's environment, particularly the emotional family climate – characterized by mood, communication patterns, and interactions among caregivers – as well as broader social contexts such as grandparents, friends, teachers, and neighbors [6]. Through these experiences, children learn to see themselves as part of a functioning community, regulate their emotions, communicate effectively, and engage in fair and prosocial behavior – a process referred to as emotional socialization [10].

Activities that strengthen the bond between caregivers, children, and their environment include shared family routines such as shared dinner, outings at the weekend, gaming, or creative projects [2, 14]. Equally important, dedicated couple time – activities shared by parents without children – which helps strengthen and stabilize the parental relationship [6].

In Tim’s family, a daily ritual takes place at dinner: they talk about the events of the day and how each person felt. This routine in a safe environment helps Tim regularly reflect on his emotions. They also meet regularly with another family for game nights, giving the children opportunities to experience and manage both success and disappointment in a playful setting. These shared experiences allow Tim to learn not only from his own parents, but also by observing the behavior of other trusted adults.

Conclusion

Emotion regulation is an essential component of childhood development. This capacity can be nurtured through consistent, supportive involvement from caregivers and opportunities to practice in everyday life. Developing emotional regulation takes time. It requires patience, ongoing support, and a willingness to stay engaged – especially when progress is slow. By guiding children toward emotions, caregivers lay the foundation for lifelong emotional strength and balance.

Bibliography

[1] J. J. Gross, "The emerging field of emotion regulation: An integrative review," Review of General Psychology, vol. 2, no. 3, pp. 271–299, 1998. doi: 10.1037/1089-2680.2.3.271.

[2] M. A. Southam-Gerow, Emotion Regulation in Children and Adolescents: A Practitioner's Guide. Guilford Press, 2013.

[3] J. Zeman, M. Cassano, C. Perry-Parrish, and S. Stegall, "Emotion regulation in children and adolescents," Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics, vol. 27, no. 2, pp. 155–168, 2006. doi: 10.1097/00004703-200604000-00014.

[4] M. J. Zimmer-Gembeck, J. Rudolph, J. Kerin, and G. Bohadana-Brown, "Parent emotional regulation: A meta- analytic review of its association with parenting and child adjustment," International Journal of Behavioral Development, vol. 46, no. 1, pp. 63–82, 2022. doi: 10.1177/01650254211051086.

[5] A. Lovis-Schmidt, L. Ackermann, S. Wascher, and H. Rindermann, "Programs to promote emotional competencies in middle childhood: A meta-analysis," Zeitschrift für Pädagogische Psychologie (Journal of Educational Psychology), pp. 1–16, 2023. doi: 10.1024/1010-0652/a000371.

[6] A. S. Morris, J. S. Silk, L. Steinberg, S. S. Myers, and L. R. Robinson, "The role of the family context in the development of emotion regulation," Social Development, vol. 16, no. 2, pp. 361–388, 2007. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9507.2007.00389.x.

[7] J. W. Pennebaker and S. K. Beall, "Confronting a traumatic event: Toward an understanding of inhibition and disease," Journal of Abnormal Psychology, vol. 95, no. 3, pp. 274–281, 1986. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.95.3.274.

[8] P. Sedlmeier et al., "The psychological effects of meditation: A meta-analysis," Psychological Bulletin, vol. 138, no. 6, pp. 1139–1171, 2012. doi: 10.1037/a0028168.

[9] S. Forstmeier and A. Maercker, "Formen des Lebensrückblicks," in Der Lebensrückblick in Therapie und Beratung. Ansätze der Biografiearbeit, Reminiszenz und Lebensrückblicktherapie [Life Review in Therapy and Counseling. Approaches to Biographical Work, Reminiscence, and Life Review Therapy], S. Forstmeier and A. Maercker, Eds. Springer, pp. 31–58, 2024. doi: 10.1007/978-3-662-68077-3.

[10] Z. B. Kakhki, A. Mashhadi, S. A. A. Yazdi, and S. Saleh, "The effect of Mindful Parenting Training on parent–child interactions, parenting stress, and cognitive emotion regulation in mothers of preschool children," Journal of Child and Family Studies, vol. 31, no. 11, pp. 3113–3124, 2022. doi: 10.1007/s10826-022-02420-z.

[11] C. Sell, H. Möller, and C. Benecke, Emotion Regulation and Coaching. Springer, 2022. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-81938-5_24.

[12] B. Paley and N. J. Hajal, "Conceptualizing emotion regulation and co-regulation as family-level phenomena," Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, vol. 25, no. 1, pp. 19–43, 2022. doi: 10.1007/s10567-022-00378-4.

[13] G. England-Mason, K. Andrews, L. Atkinson, and A. Gonzalez, "Emotion socialization parenting interventions targeting emotional competence in young children: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials," Clinical Psychology Review, vol. 100, p. 102252, 2023. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2023.102252.

[14] J. Hoffmann and S. Russ, "Pretend play, creativity, and emotion regulation in children," Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts, vol. 6, no. 2, pp. 175–184, 2012. doi: 10.1037/a0026299.

Figures

Figure 1: https://pixabay.com/de/photos/m%C3%A4dchen-baum-drau%C3%9Fen-kind-3402351/

Figure 2: Own’s Illustration

Figure 3: Own’s Illustration

Figure 4 : https://pixabay.com/de/photos/teamgeist-zusammenarbeit-2447163/