Changing the world through activism: what, why, and how

Activism involves taking action to challenge oppressive systems and create a just world for all. While there are potential harms to activism, there are many potential benefits as well. We have the power to create change through collective action. This article explores the significance and components of activism through the story of Katniss in The Hunger Games.

Figure 1: A crowd of diverse people stand with signs reading, “Justice for George Floyd,” “BLM,” “Is this the American dream?” “White silence is violence,” “My skin is not a crime,” and “defund the police.”

Figure 1: A crowd of diverse people stand with signs reading, “Justice for George Floyd,” “BLM,” “Is this the American dream?” “White silence is violence,” “My skin is not a crime,” and “defund the police.”

In the Hunger Games fictional world, we witness the Capitol's control over the poorer districts, unfairly using their resources and labor for the benefit of the privileged few while denying the other districts access. When the people across the districts revolted against the Capitol's oppressive system, the Capitol leadership responded with brutality to preserve its power. Even the Hunger Games competition itself - a deadly contest imposed by the Capitol, forcing children from the poorer districts to fight each other - served this purpose, instilling fear and conflict in the districts.

What we see in the Hunger Games is not entirely fictional. In reality, systems of oppression such as class inequity shape social values and practices that cause widespread suffering. These systems normalize unequal access to resources and cultivate a sense of powerlessness among marginalized groups [1, 2]. For example, people in Katniss’s district, the protagonist’s hometown, did not perceive themselves as capable of addressing class inequity. Being sent to die in the Hunger Games as entertainment for the rich sent a clear message: their lives did not matter. Over time, this kind of message can lead people to believe they have no power to change their situation. It makes them more vulnerable to social exclusion and economic pressure, and more likely to accept poor working conditions or limited choices [3].

What is activism?

Given the harms of oppression, how can we address it? Activism - collective actions driven by a shared commitment to liberation - is crucial for transforming societal structures and institutions into a more just society [1, 4, 5]. While activism can look different depending on an individual’s capacity and opportunities [4], it ultimately involves action oriented toward restructuring society into alternative social relations, values, and practices that honor everyone’s humanity [5]. For example, people from various districts in the Hunger Games unite despite harsh consequences when pursuing their shared goal of dismantling the Capitol due to the oppression. Activism examples include political participation (e.g., joining protests or organizing campaigns to boycott companies using unjust practices) or organizing groups to cause social change (e.g., forming a union to secure fair wages and treatment) [5,9]. Since these actions require specialized knowledge, skills, and resources, activism requires building collective capacity, such as community organizing, training, and mobilization [5].

Advocacy versus activism

While this article focuses on activism, it is important to acknowledge that advocacy can also foster change, lay the foundation for activism, and offer an alternative when activism is unfeasible [9]. Similar to activism, advocacy exists on a spectrum that involves mobilizing people and groups to draw attention to specific issues and influence decision-making processes [9]. Advocacy focuses on working within existing systems to amplify support for social and political causes, often at lower risk and cost, while activism involves acting outside of established systems to transform them, often at higher risk and cost [9]. Advocacy might look like putting a bumper sticker on your car (symbolic advocacy), or talking to friends about an important issue (communicative advocacy) [9]. For Katniss, advocacy was creating a symbol of resistance, holding up her three fingers, to create awareness of class inequity. While these actions may seem small, they can spread ideas that create waves of cultural change by holding systems and their members accountable for the wellness and liberation for all [2, 9].

A helpful way to think about advocacy and activism is to imagine you are on a moving walkway that has always been heading in a harmful direction, negatively impacting you and others on it. Standing still on the moving walkway maintains harm. Advocacy is walking against the walkway’s motion and encouraging others to join you as an important first step toward change. Activists step off the walkway and work together to replace the walkway with an improved transportation option.

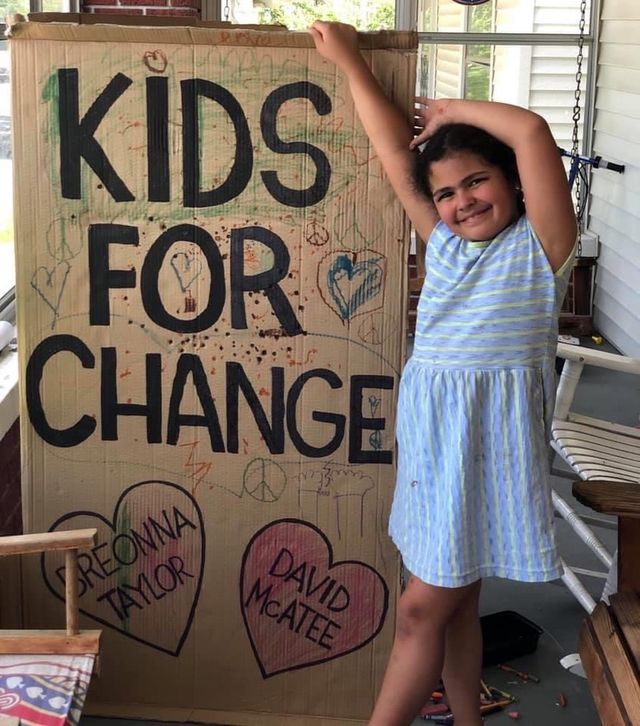

Figure 2: A child poses next to her poster stating 'Kids for Change' for a Louisville protest against police shootings of Black people in June 2020. Breonna Taylor and David McAtee's names are written in hearts.

Figure 2: A child poses next to her poster stating 'Kids for Change' for a Louisville protest against police shootings of Black people in June 2020. Breonna Taylor and David McAtee's names are written in hearts.

Why be an activist?

Activism heals. Activism not only works to transform oppressive systems but also fosters liberation from internalized oppression by cultivating critical consciousness, nurturing hope, reclaiming culture and strengths, and strengthening community connections [2, 7]. Other psychological benefits from activism can include greater self-understanding, reduced shame, and enhanced relational skills like boundary setting and communication, as gender-diverse survivors involved in anti-sexual assault activism reported [8]. Activists also shared that receiving support from fellow activists and contributing to the healing of others played a meaningful role in their own healing processes, fostering a deeper recognition of their self-worth and strengths [8]. One deeply healing moment in the Hunger Games occurs when Katniss honors the death of a fellow tribute, a young girl named Rue, by covering her with flowers – a profoundly humanizing act that resists the Capitol’s dehumanization of tributes. By mourning Rue with care and love, Katniss affirms Rue’s dignity and reclaims the humanity of all tributes, including her own. Viewers recognize this act as one of solidarity and resistance, and its emotional impact sparks a rebellion against their continued oppression.

How do we be activists?

Ingredients of activism

Taking action against oppression is not typically taught and involves inherent risks. As such, it takes time, experience, and some key ingredients to develop the capacity to act. In their framework of radical healing, French and colleagues [7] argue that critical consciousness, a concept introduced by Paulo Freire [10], is essential for activism. Critical consciousness is a cyclical process of critical reflection and action, in which individuals, often with others, develop the awareness and political efficacy needed to question and transform systems that disempower them [10,11]. Researchers found that activists used this process to deepen their understanding of power, shaped by their experiences with oppression and privilege, and applied this new awareness to strengthen their agency and knowledge of change opportunities [4]. This ongoing understanding of power helps activists engage in activism more effectively, allowing them to honor their capacity while actively seeking opportunities to build the resources necessary to sustain their activism in the long term [4,5]. For example, Katniss’s experiences in the Hunger Games and her interactions with tributes from other districts expose her to the ways class inequality operates. This growing awareness ultimately shapes her resistance to the Capitol’s exploitative system and informs the development of her strategies for resistance.

In addition to critical consciousness, the radical healing framework lists radical hope, cultural reclamation, and strengthened community ties as critical for activism to be effective [7]. They emphasize that radical hope is crucial because it enables individuals to believe their fight for justice contributes to the possibility of liberated futures [7]. They also stress the importance of recognizing the strength of those actively resisting oppression, reflecting their refusal to let injustice define their lives and their pursuit of joy [7]. Returning to one’s cultural and ancestral roots is vital for empowering individuals to reclaim cultural knowledge and define themselves beyond their oppressors [7]. Lastly, they argue that collective action requires a strong connection to one’s community where individuals can find refuge and solidarity amid oppression [7].

Figure 3: A birds-eye view of a mural that reads “End Racism now” painted yellow onto street pavement.

Figure 3: A birds-eye view of a mural that reads “End Racism now” painted yellow onto street pavement.

Barriers to activism

While activism can be healing, there are also risks. Activists often face challenges pursuing justice, such as mental harm due to repeated exposure to danger and stress [12]. For example, Katniss was put under increased governmental surveillance, forced to participate in a second Hunger Games competition, and faced threats to her and her family’s safety due to her growing visibility as a symbol of resistance. In the real world, social justice activists frequently experience burnout, where they feel overwhelmed, isolated, disillusioned, exhausted, and powerless [12]. This burnout often causes withdrawal from activism and declining physical and emotional health [12]. While activism is meaningful and rewarding, activists highlighted that the slow pace of progress, lack of support, reluctance of others to join, retraumatization, and bureaucratic challenges can trigger feelings of defeat and pointlessness [8].

Additionally, activist communities can reproduce oppressive structures when privilege goes unrecognized and harms members with marginalized identities [12]. For example, activists with relative economic privilege may inadvertently silence others from economically marginalized backgrounds who often hold other marginalized identities, such as race and disability [12]. Those with greater resource access, like healthcare and job security, can commit more time to activism, while a lack of these resources can significantly limit lower-income activists’ and activists of color’s ability to engage in activism, further marginalizing them [12]. Unchecked privilege in activist spaces is problematic because it risks overlooking the needs and perspectives of the most vulnerable, failing to consider their liberation as integral to collective liberation. For activism to be liberatory, the founding principles of a social movement should be actively anti-oppressive and inclusive [6].

Figure 4: The backs of two people walking away from the camera. Both are wearing rainbow-patterned clothes and one is wearing a flag that reads, “Love is love.”

Figure 4: The backs of two people walking away from the camera. Both are wearing rainbow-patterned clothes and one is wearing a flag that reads, “Love is love.”

Centering care in activism

To address the emotional and physical demands of activism, researchers have identified individual and collective care strategies that are critical for activists to succeed [8,12]. Often, activists neglect self-care, worsening the challenges of activism and contributing to burnout. The culture of selflessness common in activist communities can lead individuals to view self-care as "self-indulgent" or a "distraction" from the cause [13]. However, self-care is not only vital for personal well-being but also crucial for sustaining long-term activism, especially within systems that fail to care for us [13]. After all, there can be no meaningful action without the people who propel movements forward. On an individual level, self-care may include setting personal boundaries, such as being mindful of one’s capacity and knowing when to step back, identifying one’s purpose, building one’s activist identity, celebrating “small wins,” and prioritizing personal well-being [8, 12]. Collective strategies include seeking support through relationships, such as leaning on friends or seeking counseling, fostering community connections, and prioritizing collective care [8, 12]. For Katniss, self-care takes the form of seeking solace in nature for grounding, nurturing connections with loved ones and comrades for emotional support, and allowing herself space to grieve the losses she endures.

Activists with multiple marginalized identities often face added risks due to the intersecting systems of oppression they navigate. [12,13]. Collective care is a powerful way for historically marginalized communities to heal the social and mental connections broken by systems of oppression, reconnecting communities of care that cultivate collective action and wellness [14]. For example, antidotes to the violence affecting Black youth include cultivating caring relationships, revitalizing community life, and embracing their culture, which help them develop awareness of systemic injustices and build the capacity to resist racial violence [14]. Similarly, activists with marginalized identities can adopt creative self-care methods to support their well-being. These strategies include creating art to express and process emotions, practicing mindfulness to stay attuned to oneself, building supportive communities, exploring alternative and more accessible methods like digital activism to engage in direct action, knowing and asserting one's rights to minimize harm during direct action, and focusing on thriving, not just surviving, by living in alignment with one’s values [13].

Figure 5: Children and adults gather with posters to protest police shootings of Black people in a Louisville neighborhood with signs reading, 'Kids for Change' and 'Black Lives Matter' in June 2020. Breonna Taylor and David McAtee's names are written in hearts.

Figure 5: Children and adults gather with posters to protest police shootings of Black people in a Louisville neighborhood with signs reading, 'Kids for Change' and 'Black Lives Matter' in June 2020. Breonna Taylor and David McAtee's names are written in hearts.

Take home message

Activism is collective action rooted in a shared commitment to liberation and the dismantling of all forms of oppression [1, 4, 5]. Unlike advocacy, which often serves as an initial step towards change by drawing attention to inequities, activism seeks to create deeper relational and structural change. Activism offers both personal and collective benefits, both by transforming external harmful systems and alleviating disempowering conditions. Key ingredients that support activism include critical consciousness, radical hope, cultural reclamation, recognition of personal and collective strengths, and strengthened community ties. While activism carries risks such as retraumatization and the potential to reproduce oppressive dynamics, centering individual and collective care can strengthen the benefits and sustainability of activism.

Activism creates a more just world as our actions hold immense power. Activism, like any skill, grows with practice. Start small. Choose manageable steps and gradually expand your efforts, reflecting on your growth. Collaborate with others, anticipate potential barriers, and approach challenges with strategic preparation. Consistently examine your positionality, strengths, resources, and risks to determine your effective roles and actions. For additional guidance, explore resources like the Activist Handbook, a dynamic, collaborative tool with activism examples and guides [15]. As philosopher and political activist Dr. Cornel West reminds us, “Justice is what love looks like in public.” In this sense, activism becomes an act of public love – a powerful force for co-creating just worlds. Given the centrality of activism to collective liberation and wellness, we invite you to reflect: If not now, when? If not us, who?

Bibliography

[1] I. Martín-Baró, Writings for a Liberation Psychology. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1994.

[2] I. Prilleltensky, "The role of power in wellness, oppression, and liberation: The promise of psychopolitical validity," J. Community Psychol., vol. 36, no. 2, pp. 116–136, 2008. doi: 10.1002/jcop.20225

[3] L. Esposito and F. M. Perez, "Neoliberalism and the commodification of mental health," Humanity & Society, vol. 38, no. 4, pp. 414–442, 2014. doi: 10.1177/0160597614544958

[4] C. R. Collins, D. Kohfeldt, and M. Kornbluh, "Psychological and political liberation: Strategies to promote power, wellness, and liberation among anti‐racist activists," J. Community Psychol., vol. 48, no. 2, pp. 369–386, 2020. doi: 10.1002/jcop.22259

[5] R. J. Watts, N. C. Williams, and R. J. Jagers, "Sociopolitical development," American Journal of Community Psychology, vol. 31, no. 1–2, pp. 185–194, 2003.

[6] C. Berlet, "Hate, oppression, repression, and the apocalyptic style," Journal of Hate Studies, vol. 3, no. 1, pp. 145–166, 2003.

[7] B. H. French et al., “Toward a psychological framework of radical healing in communities of color,” The Counseling Psychologist, vol. 48, no. 1, pp. 14–46, May 2020, doi: 10.1177/0011000019843506.

[8] C. Strauss Swanson and D. M. Szymanski, “From pain to power: An exploration of activism, the #Metoo movement, and healing from sexual assault trauma.,” Journal of Counseling Psychology, vol. 67, no. 6, pp. 653–668, Mar. 2020, doi: 10.1037/cou0000429.

[9] B. W. McKeever, R. McKeever, M. Choi, and S. Huang, “From Advocacy to Activism: A Multi-Dimensional scale of communicative, collective, and combative behaviors,” Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, vol. 100, no. 3, pp. 569–594, Mar. 2023, doi: 10.1177/10776990231161035.

[10] P. Freire, Pedagogy of the Oppressed. New York, NY: Continuum, 1970.

[11] R. J. Watts, M. A. Diemer, and A. M. Voight, “Critical consciousness: Current status and future directions,” New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development, vol. 2011, no. 134, pp. 43–57, Dec. 2011, doi: 10.1002/cd.310.

[12] P. C. Gorski and C. Chen, “‘Frayed All Over:’ The causes and Consequences of activist burnout among social justice education activists,” Educational Studies, vol. 51, no. 5, pp. 385–405, Sep. 2015, doi: 10.1080/00131946.2015.1075989.

[13] M. M. Elnakib and M. Turner, “The Power of Activism as Self-Care: An autoethnography of the arrest of activists in the wake of the George Floyd protests,” Women & Therapy, vol. 46, no. 4, pp. 391–406, Oct. 2023, doi: 10.1080/02703149.2023.2286056.

[14] S. A. Ginwright, “Peace out to revolution! Activism among African American youth,” Young, vol. 18, no. 1, pp. 77–96, Feb. 2010, doi: 10.1177/110330880901800106

[15] Activist Handbook and Federation of Young European Greens, Activist Handbook. [Online]. Available: https://activisthandbook.org/. [Accessed: Jan. 15, 2025].

Pictures

Figure 1: Pexels

Figure 2: Taken and owned by the third author, Miranda Willians

Figure 3: Pexels

Figure 4: Pexels

Figure 5: Taken and owned by the third author, Miranda Willians