How deliberate forgetting might lead to false memories

Reviewers: Ahmad Shahvaroughi & Undisclosed Reviewer.

Editorial Assistant: Zoey Chapman.

Ever wondered what happens when you try to forget something? Discover whether the effort to suppress memories can actually twist what you remember. This article explores the relationship between motivated forgetting and false memory formation, revealing its crucial impact in the legal arena.

In 2016, the sports world was rocked by the largest sexual abuse scandal in sports history [1]. In the highly publicized Larry Nassar case, numerous women, including prominent Olympic gymnasts such as Simone Biles and Aly Raisman, courageously came forward with allegations of sexual abuse against the former USA Gymnastics team doctor, spanning over two decades. Nassar was accused of exploiting his position of trust to sexually assault many young female athletes under the guise of medical treatment. The women recounted instances of Nassar's abuse occurring during medical examinations, often in private settings. Nassar was eventually sentenced to 40 to 175 years behind bars.

Delayed reporting in cases of historical sexual abuse, due to the passage of time and lack of contemporaneous evidence, casts doubt on the validity of the memories. By validity, we refer to the accuracy of the memories recalled by the witness. Some survivors in Nassar’s case reported that they had intentionally tried to forget memories of the abuse for years before coming forward, attributing this to feelings of shame, fear of reprisal, self-blame, and the normalization of Nassar's behavior within the gymnastics community [1]. Despite Nassar's sentencing, a crucial question persists in many historical abuse cases: How accurate are the recalled memories given the passage of time and the absence of contemporaneous evidence? Furthermore, could the act of attempting to forget contribute to the creation of false memories (i.e., memories of details that were not experienced), thereby diminishing the validity of statements? To explore this issue, we will first discuss the concepts of motivated forgetting and false memory and then elaborate on the link between the two.

Motivated Forgetting

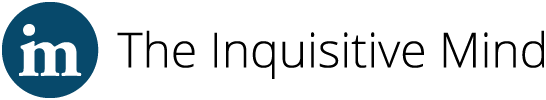

Forgetting can occur as a normal process where memories naturally fade [2]. The forgetting curve, originally described by Ebbinghaus [2], describes the exponential decay of memory retention over time following initial learning (see Figure 1, [3]). Ebbinghaus found a rapid decline in memory retention shortly after learning, followed by a more gradual decrease over subsequent intervals. This aspect of memory reminds us that our recollections are not static but rather dynamic and subject to change over time.

Figure 1: The Forgetting Curve. Note: Percentage of correct recognition of studied stimuli days after learning.

Figure 1: The Forgetting Curve. Note: Percentage of correct recognition of studied stimuli days after learning.

On the other hand, forgetting can also happen when people actively try to suppress memories they do not want (see Figure 2), also known as motivated forgetting [4]. This process often occurs in response to memories that are distressing, traumatic, or unbearable. One victim in the Nassar case, reflecting on the trauma after two decades, said, “I felt dizzy, like I would vomit.” These overwhelming emotions can lead individuals to suppress their memories to reduce feelings of disgust, fear, anxiety, or, paradoxically, even shame [1]. Outside of the Nassar case, imagine someone who has experienced a severe car accident. Recalling the details of the accident, such as the sight of a dead person, can trigger profound feelings of fear, anxiety, or even guilt. These emotions may be so overwhelming that the individual may engage in motivated forgetting to suppress memories to avoid experiencing the associated distress. Such efforts, however, are not always successful. For example, for people with post-traumatic stress disorder, it is difficult to forget traumatic events [5], which can seriously affect their daily lives and cause extreme distress.

Figure 2: Motivated Forgetting

Figure 2: Motivated Forgetting

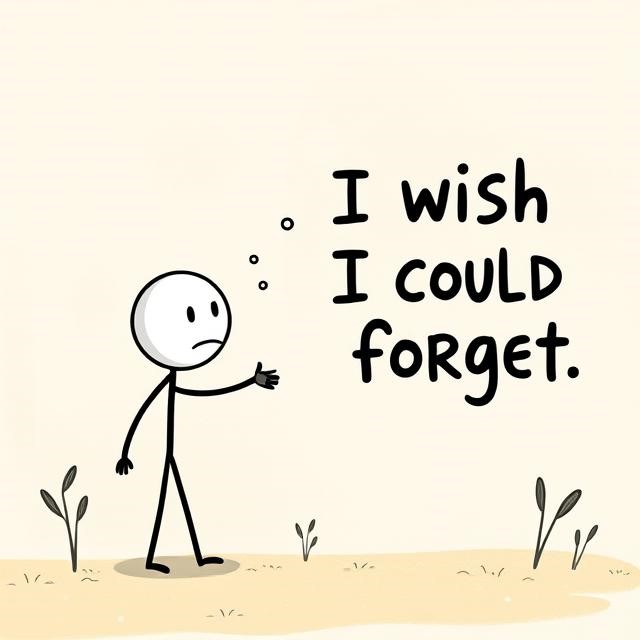

Researchers have been trying to study cases of

motivated forgetting with lab-created materials, such as word lists. Researchers frequently use a technique called the

Think/No-Think (TNT) paradigm [6] (see Figure 3) to mimic the way

motivated forgetting works in real-world situations. Participants are first shown pairs of words, like "Cloud-Tree," and they learn them together. Later, they are shown just the

cue word (i.e., "Cloud") and asked to either think about the target word (i.e., “Tree”) or to try hard not to think about it. Then, they are tested to examine how well they remember the target word when they are shown the first one again. Studies have found that unwanted memories can be efficiently suppressed, which is indicated by a higher

recall of targets in the think group than the no-think group [4,6].  Figure 3: The Think/No-Think Paradigm Procedure

Figure 3: The Think/No-Think Paradigm Procedure

Another paradigm used to investigate motivated forgetting is the directed forgetting paradigm [7]. Participants are initially presented with learning materials (e.g., a list of words) to remember. They are then instructed either to remember or forget the items on the list. Subsequently, a second list of items is presented to them. Following this, participants undergo a memory test. Notably, participants instructed to forget the first list typically demonstrate poorer recall of its contents compared to those instructed to remember it. These lab findings should be interpreted with caution because the forgetting effects are observed using rather simple neutral materials. An interesting question is whether this desire to forget also adversely affects the reliability of witness statements?

Previous studies have shown that many different factors can distort memory resulting in false memories [8]. This is a significant issue in legal cases where alleged victims sometimes report experiences that supposedly happened many years ago [9]. Could the memories of those who have engaged in forgetting practice contain more false memories than individuals who did not attempt to forget?

False Memory

False memory refers to the remembrance of an entire event or a detail of an event that was not experienced [10]. False memories can have profound implications, sometimes even leading to false accusations and wrongful convictions in legal proceedings. The case of Melvin Quinney is a striking example of how false memories can lead to wrongful convictions. In 1990, Quinney was arrested for sexually abusing his son John and daughter Sarah. John’s memories of being abused and satanic rituals developed after going through weeks of suggestive questioning by therapists and law enforcement officials. Despite his innocence, Quinney was convicted in 1991, sentenced to 20 years, and served 8 years in prison. John later realized that these memories were actually false memories and started to clear his father’s name. Finally, Quinney was exonerated in 2023 [9].

Psychologists have devised different procedures to elicit false memories of details in the lab [10]. The implantation method is used to induce false memories of autobiographical events. In this procedure, experimenters attempt to implant an entire false event into the memory of participants. Participants’ parents first confirm that the participants never experienced the false event (e.g., lost in the shopping mall). Later, false information is repeatedly suggested to participants by experimenters across multiple sessions [10]. Eventually, Scoboria and colleagues conducted a mega-analysis and found a false memory rate at around 30% across reports from 8 studies, which rose to 46% when combining techniques (i.e., imagination, providing self-relevant information, and providing suggested descriptions) [11,12]. This paradigm has been used successfully across various events and diverse age groups.

The misinformation method arises from failures in source monitoring, where individuals misattribute the origin of information. In the misinformation paradigm, participants are presented with stimuli (e.g., a video of a traffic accident) and then receive misinformation (e.g., that the police arrived while this was not in the video). Finally, participants receive a memory task where a significant proportion of them typically report having seen the misinformation during the encoding of the event, an effect termed the misinformation effect [10]. This paradigm has been effective with various populations such as children, older adults, people with relatively low intelligence and poor perceptual abilities, and intoxicated samples [10]. Its application has also been extended to virtual reality settings. The implantation and misinformation paradigms show that memory accounts can be contaminated by suggestions.

However, research also shows that false memories of details can arise spontaneously without any external suggestion [10]. One paradigm used to examine such spontaneous false memories is the Deese/Roediger-McDermott (DRM) paradigm. In this paradigm, participants are presented with lists of associatively related words (e.g., jail, sentence, missing, etc.). Later memory tasks reveal that individuals often recall and recognize a non-presented but related word, known as the critical lure (e.g., thief). Besides using word lists, researchers have also shown the production of spontaneous false memories with stimuli that more closely simulate real-world situations, such as visual scenes and videos [10]. This paradigm is particularly informative because it illustrates how false memories can emerge at the level of specific details. While participants might accurately remember the general theme of an event, they may mistakenly recall a specific detail that was never presented.

False Memory Theories

Activation Association Theory (AAT) posits that individuals' knowledge base or networks of information stored in their minds consists of interconnected nodes containing varying degrees of information. When an event is experienced, these interconnected nodes become activated, potentially leading to the generation of false memories [13]. For instance, after witnessing a car accident, a person may mistakenly recall seeing a stop sign at the intersection, even though there was none. This false memory could arise because the concept of a stop sign is strongly associated with the context of traffic accidents, leading to its activation and subsequent incorporation into the person's memory of the event.

Fuzzy Trace Theory (FTT) stipulates that two memory traces are involved in the creation of false memory [8]. According to this theory, verbatim traces encode the exact details of an experience, while gist traces capture the underlying meaning. As verbatim traces are more prone to forgetting, gist traces become the primary source of memory retrieval as time elapses. Consequently, reliance on gist traces during memory retrieval can sometimes lead to the formation of false memories, as individuals may reconstruct past events based on the general meaning rather than specific details. Consider the example of a witness to a car accident again. While the witness may accurately remember specific details such as the color of the cars involved, the location of the accident, and the weather conditions (encoded in verbatim traces), they may also form a gist memory of the event, such as the overall chaotic nature of the scene. However, over time, as verbatim traces fade, the witness may rely more heavily on the gist memory of the event. This could lead the witness to incorrectly remember seeing broken glass or hearing screeching tires, even if those details were not present in the actual event. Interestingly, the two theories (FTT and AAT) offer competing views on how natural forgetting and attempts to forget might affect the formation of false memories. Other theories exist that can also explain the formation of false memories. For example, the Source Monitoring Framework suggests that false memories arise from errors in identifying the origin of a memory, such as mistaking a suggested detail for a real event [14]. This theory plays a central role in understanding phenomena like the misinformation effect, where post-event information is incorrectly remembered as part of the original event due to source monitoring failures.

The AAT proposes that when we encode an event, our memory automatically activates related concepts, resulting in spontaneous false memory. Suppressing memory from coming to mind may stop the activation of associated concepts. Therefore, according to AAT, motivated forgetting might either not influence or reduce the likelihood of remembering events that did not occur. Conversely, FTT suggests that when we are reminded of something, our memory retrieves both specific details (verbatim) and the general meaning ( gist) associated with the event. When we actively suppress certain details, we may rely more on the general meaning, potentially leading to the formation of false memories. Therefore, according to FTT, both natural and motivated forgetting could inadvertently increase the likelihood of erroneously remembering suppressed information later on. Thus, both theories provide competing predictions regarding the impact of natural and motivated forgetting on false memory formation.

Will motivated forgetting lead to false memories?

Studies have shown different patterns concerning the link between motivated forgetting and false memory [15-18]. Forgetting was found to increase false memories, for example, in a study of Pitarque and colleagues [16]. In this study, participants first learned two lists of 18 words, each composed of three sets of six associatively related words, using a DRM-style word list test. After studying the first list, one group of participants was instructed to suppress their memory of the first word list before moving on to the second list. Finally, they went through a memory recall test. It was found that participants who were instructed to forget the first list ended up correctly recalling fewer learned words and falsely recalling more critical words than participants receiving instructions to remember the word lists. In another study [17], participants who suppressed their memory of a film falsely recognized more non-important details than participants who did not suppress their memories.

Motivated forgetting has also been found to decrease [15] or not affect [18] false memory creation. For instance, Howe [15] examined the relationship between motivated forgetting and the formation of false memories in children. Children aged five to eleven years old were assigned to different groups to study a DRM list. Before they moved on to learn the second DRM list, one group received forgetting instructions to forget the first list, while the other group received remembering instructions. Subsequently, they were asked to recall the words from the lists. It was found that the instruction of forgetting resulted in a reduction of false memories in comparison to the instruction of remembering.

These findings show that while some studies have demonstrated an increase in false memories following motivated forgetting, others have shown either a decrease or no significant relationship. The different types of false memory types might be one reason for the inconsistent results. For example, Mazzoni [19] distinguished between naturally occurring and suggestion-dependent false memories, which have been shown to be empirically unrelated [20-22]. Besides, mechanisms linking forgetting to false memory formation may differ between children and adults, resulting in divergent findings. For example, Howe [15] demonstrated that false memories in children instructed to forget DRM lists may arise from more conscious and effortful processes. In contrast, adults’ false memories appear to result from relatively automatic semantic activation. The mixed pattern of results can also potentially be attributed to factors like differences in the participant sample, testing different groups under one condition versus testing the same group under multiple conditions, and variations in the stimulus/tasks employed.

Implications and Conclusions

Understanding the relationship between motivated forgetting and false memory carries significant importance, especially within legal contexts where the validity of witness testimonies is crucial. Expert witnesses tasked with providing a statement on how forgetting might impact false memory should draw as thorough a picture as possible. For example, this can occur when adults are instructed to forget rather than remember, as demonstrated in studies using the combined DRM and directed forgetting paradigms [13]. In contrast, under other conditions, forgetting may reduce false memories, as seen when children undergo the same DRM and directed forgetting procedures [13]. By presenting a comprehensive statement, expert witnesses can assist legal professionals in grasping the complex nature of the link between forgetting and false memories and making precise judgments. However, our understanding of this relationship is still evolving. Current research, though insightful, is insufficient to fully capture the complexity of how forgetting influences false memory. Further studies are needed to clarify this link and improve the accuracy of expert testimony in legal contexts.

In summary, this article has delved into the link between motivated forgetting and false memory formation. Existing research has shown inconsistent results, likely related to the diverse methods used in the studies, highlighting the need for continued investigation. This article provides valuable insights into how motivated forgetting can affect false memories, showing that effects strongly depend on factors like the context of the event. As our understanding of the relationship between motivated forgetting and false memory continues to evolve, ongoing research is crucial for refining legal practices and ensuring the accuracy of witness testimonies. This article contributes to that effort by highlighting the complex and context-dependent nature of this relationship.

Bibliography

[1] A. Wellman, M. Bisaccia Meitl, P. Kinkade, and A. Huffman, "Routine activities theory as a formula for systematic sexual abuse: A content analysis of survivors’ testimony against Larry Nassar," American Journal of Criminal Justice, vol. 46, no. 2, pp. 317–344, 2021.

[2] H. Ebbinghaus, " Memory: A contribution to experimental psychology," Annals of Neurosciences, vol. 20, no. 4, pp. 155–156, 2013.

[3] Y. Zhang, H. Otgaar, R. A. Nash, and L. Rosar, "Time and memory distrust shape the dynamics of recollection and belief-in-occurrence," Memory, vol. 32, no. 4, pp. 484–501, 2024.

[4] M. C. Anderson and S. Hanslmayr, "Neural mechanisms of motivated forgetting," Trends in Cognitive Sciences, vol. 18, no. 6, pp. 279–292, 2014.

[5] R. J. McNally, L. J. Metzger, N. B. Lasko, S. A. Clancy, and R. K. Pitman, "Directed forgetting of trauma cues in adult survivors of childhood sexual abuse with and without posttraumatic stress disorder," Journal of Abnormal Psychology, vol. 107, no. 4, pp. 596–601, 1998.

[6] M. C. Anderson and C. Green, "Suppressing unwanted memories by executive control," Nature, vol. 410, no. 6826, pp. 366–369, 2001.

[7] B. H. Basden, D. R. Basden, and G. J. Gargano, "Directed forgetting in implicit and explicit memory tests: A comparison of methods," Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, vol. 19, no. 3, pp. 603–616, 1993.

[8] C. J. Brainerd and V. F. Reyna, The Science of False Memory. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2005.

[9] M. L. Howe and L. M. Knott, "The fallibility of memory in judicial processes: Lessons from the past and their modern consequences," Memory, vol. 23, no. 5, pp. 633–656, 2015.

[9] Innocence Project of Texas, "Melvin Quinney," 2023. [Online]. Available: https://innocencetexas.org/cases/melvin-quinney-2/.

[10] H. Otgaar, S. T. L. Houben, and M. L. Howe, "Methods of studying false memory," in Handbook of Research Methods in Human Memory, H. Otani and B. L. Schwartz, Eds. Routledge, pp. 238–252, 2019.

[11] A. Scoboria, K. A. Wade, D. S. Lindsay, T. Azad, D. Strange, J. Ost, and I. E. Hyman, "A mega-analysis of memory reports from eight peer-reviewed false memory implantation studies," Memory, vol. 25, no. 2, pp. 146–163, 2017.

[12] R. Arce, A. Selaya, J. Sanmarco, and F. Fariña, "Implanting rich autobiographical false memories: Meta-analysis for forensic practice and judicial judgment making," International Journal of Clinical and Health Psychology, vol. 23, no. 4, p. 100386, 2023.

[13] M. L. Howe, M. C. Wimmer, N. Gagnon, and S. Plumpton, "An associative-activation theory of children’s and adults’ memory illusions," Journal of Memory and Language, vol. 60, pp. 229–251, 2009.

[14] M. K. Johnson, S. Hashtroudi, and D. S. Lindsay, " Source monitoring," Psychological Bulletin, vol. 114, no. 1, pp. 3–28, 1993.

[15] M. L. Howe, "Children (but not adults) can inhibit false memories," Psychological Science, vol. 16, no. 12, pp. 927–931, 2005.

[16] A. Pitarque, E. Satorres, J. Escudero, S. Algarabel, O. Bekkers, and J. C. Meléndez, " Motivated forgetting reduces veridical memories but slightly increases false memories in both young and healthy older people," Consciousness and Cognition, vol. 59, pp. 26–31, 2018.

[17] J. M. Oulton, D. Strange, and M. K. Takarangi, " False memories for an analogue trauma: Does thought suppression help or hinder memory accuracy?," Applied Cognitive Psychology, vol. 30, no. 3, pp. 350–359, 2016.

[18] L. M. Knott, M. L. Howe, M. C. Wimmer, and S. A. Dewhurst, "The development of automatic and controlled inhibitory retrieval processes in true and false recall," Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, vol. 109, no. 1, pp. 91–108, 2011.

[19] G. Mazzoni, "Naturally occurring and suggestion-dependent memory distortions: The convergence of disparate research traditions," European Psychologist, vol. 7, no. 1, pp. 17–30, 2002.

[20] J. Ost, H. Blank, J. Davies, G. Jones, K. Lambert, and K. Salmon, " False memory ≠ false memory: DRM errors are unrelated to the misinformation effect," PLoS ONE, vol. 8, no. 4, pp. e61406, 2013.

[21] B. Zhu, C. Chen, E. F. Loftus, C. Lin, and Q. Dong, "The relationship between DRM and misinformation false memories," Memory & Cognition, vol. 41, no. 6, pp. 832–838, 2013.

[22] D. M. Bernstein, A. Scoboria, L. Desjarlais, and K. Soucie, "“False memory” is a linguistic convenience," Psychology of Consciousness: Theory, Research, and Practice, vol. 5, no. 2, pp. 161–179, 2018.

Figure Sources

Figure 1: Adapted from “Time and memory distrust shape the dynamics of recollection and belief-in-occurrence” by Zhang, Y., Otgaar, H., Nash, R. A., and Rosar, L, 2024, Memory, 32(4), 484–501.

Figure 2: The author Yiwen Zhang created the picture with DeepAI.

Figure 3: The author Yiwen Zhang created the picture.

article author(s)

article keywords

article glossary

- motivated forgetting

- false memory

- shame

- false memories

- Memory

- anxiety

- guilt

- distress

- think/no-think (TNT) paradigm

- cue

- recall

- paradigm

- desire

- factors

- significant

- misinformation

- source monitoring

- misinformation paradigm

- Encoding

- virtual reality

- spontaneous false memories

- critical lure

- gist

- Retrieval

- sample

- Stimulus

- recollection

- false memory implantation

- meta-analysis